Sleepers: The Zenith Prime

Meet the manually-wound El Primero that nobody asked for, but Zenith produced anyway.

Welcome to Sleepers – a series of articles in which I show you guys watches that you probably didn’t know existed. And just like our automotive counterpart of sleeper cars, these are watches, that, had people known about them, would have gone absolutely gaga over, to the point where if people knew that they existed, it wouldn’t take long to realize that these watches are better than their competition (and sometimes even the model line in which they are based off of) in all possible aspects. To kick this series off, I’d like to introduce you to the Zenith Prime – a watch that look like an El Primero from a distance, but is so much more than that up close. That aside, I’ll be covering all aspects of the spectrum, from divers to fliegers, dress watches to chronographs – you name it, and I’ll promise you that I’ll show you a sleeper. The best part? You can actually buy them pretty easily, as they command a price that’s far less than what they are actually supposed to be worth.

So sit back, relax, put a loupe on, and prepare to have your mind blown.

Wait. What Is The Zenith Prime?

If you know your watches, you’ll probably know that the Zenith El Primero was the first “proper” automatic chronograph. The reason why I say this is because this watch, during its time, had (and still has) the first-ever chronograph movement that was not modular, but was a chronograph movement from the ground-up. Confused? Let me explain. See, a modular chronograph movement consists of two parts – you have your base caliber, which is something that powers things like the time and date (and not much else), and you have a chronograph (stopwatch) module attached on top. What this means is that the chronograph module can be removed from the watch, and everything except the chronograph will continue to work. It’s like this – if the base caliber is the engine, then your chronograph module is the supercharger – the former works without the latter, but not vice-versa.

Now, instead of having a supercharged V8 under the hood, you have a naturally-aspirated V12. You can’t strip it into two distinct entities, because it’s just one engine. That’s what Zenith did with chronographs – it’s an automatic chronograph from the ground up, and not a modular entity. That’s why their watch was called the El Primero – or “the first”. While I don’t want to get into the history of the El Primero and how Rolex used to revive the Daytona as I’ll save that story for later, all you need to know is that it’s famous for being the world’s first automatic chronograph.

But what happens if you remove the very thing that made the El Primero famous to begin with? Does it no longer becomes an “automatic” chronograph, but a highly generic manually wound chronograph? While enthusiasts like you and I may not know the answer to this question, Zenith did. And that answer, ladies and gentlemen, is called the Zenith Prime.

The Glorious Caliber 420

Let me get this out of the way. Is this a Patek wannabe when it comes to its choice of movement? Nope. Do you want it to be one? Nope. Did the Lemania 1873 found in the Omega Speedmaster have nicer finishing? Yes. I’d argue that this looks more like a $300 Seagull than a $3,000 El Primero. On that note, let me ask you a question – can you ever name any high-end chronograph that’s not only manually wound, but has a ridiculously high beat rate of 36,000 vibrations per hour? Well, if you think I’m an idiot for making a big deal over 36,000 vibrations an hour, it’s the horological equivalent of having a glorious 9000 RPM redline. That aside, let’s play a game of top trumps.

The $40,000 Vacheron Constantin Cornes de Vache has a beat rate of 21,600 vibrations per hour. The Patek Philippe 5980 (god knows how much that thing costs as much at this point) and the $80,000 A. Lange & Söhne Datograph are both even worse in this department with 18,000 vibrations per hour. Too high a price point? Let’s level the playing field. The Omega Speedmaster Professional, like the big-boy Vacheron also has a 21,600 vibrations per hour beat rate. Of course, a high or low beat rate doesn’t necessarily say that they’re bad watches. It just shows how-well engineered this watch is.

There is no manually-wound chronograph that can come close to the beat rate of this watch. In fact, this watch was made in the 1990s, and there is not a single modern chronograph (that’s not the new El Primero) except for the Grand Seiko Tentagraph that can come close. That doesn’t count however, as that’s an automatic while this is a manual. This watch was the first and last of its kind in this aspect, and truth be told, I don’t think the combination of a manually-wound high-beat chronograph will ever be seen in the eyes of the market again.

Ultimately, if you want to beat a Zenith Prime, you gotta be a Zenith Prime. That’s it.

Other Cool Details

Well, for starters, this watch is 1.6 millimeters thinner than its automatic counterpart. That’s not much, but shaving 1.6mm off of a watch is like shaving 150 kilos out of a production car to make it more track-focused. Another beautiful thing that you may have noticed earlier is that since the automatic rotorweight is gone, you do get a much more clear view of the El Primero movement, which is a nice touch for enthusiasts who are interested to see the movement inside the watch.

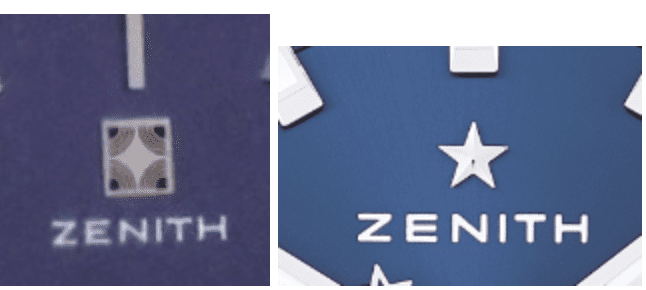

Also, this watch does utilize the old Zenith logo. Here’s a comparison of both the old and new logos for your reference:

As you can probably tell, the old Zenith logo is on the left, while the current production Zenith logo can be seen on the right-hand side. Of course, this isn’t much of a vintage reissue, but being a manually-wound chronograph, it definitely is a cool touch. The dial and hour markers are also drastically different from your standard Zenith El Primero that you’d get in the 1990s as well. In fact, the watch in general has a pretty vintage aesthetic, as certain design cues such as the rectangular pushers and an inner tachymeter scale make it look like it belongs to the 1950s or 1960s, but the modern case size of 38 millimeters makes it wear very comfortably across all wrists.

My Final Verdict

The idea of a manually-wound Zenith El Primero will offend a lot of purists. In their eyes, it is an act of absolute heresy to make arguably one of the most legendary and influential automatic (chronograph) watch movements into a manually-wound one. Here’s the thing – the manually-wound chronograph is still a bit of a rarity as far as watchmaking is concerned, and while it definitely is making its resurgence (thank Omega and Breitling for that!), it still has a long way to go before it achieves the heights of fame and appreciation that it once used to. And if ever that day comes, the 1990 Zenith Prime will be remembered as one of the greats, simply because it is the first, last, and only one of its kind. And, as a watch that hovers between the $2,500 to $4,000 range, you can get one without a waitlist (ahem, Daytona!). Sure, the movement might be difficult to service, and Zenith fanboys might even scoff at you for wearing one.

All said and done, this watch isn’t just a manually-wound Zenith El Primero. It’s a monument to Zenith’s best watchmakers, when the company was at its prime in the 1990s.

And that, my friend, is what makes this watch a bonafide sleeper.

Recommend0 recommendationsPublished in Opinion